HISTORY

Orange Aid: The Austerity Boat Race of 1944

Tim Koch of the rowing heritage website heartheboatsing.com digs out his ration book and gas mask to revisit the last time the Blues battled on the River Great Ouse.

WORDS / TIM KOCH

Oxford lead Cambridge in the 1944 Boat Race

One of the popular images of wartime Britain is that the embattled nation “kept calm and carried on”. In reality, there was much confusion and debate over what exactly should – and what should not – “carry on” during the nation’s darkest hour.

Wartime sporting events, especially those that attracted large numbers of spectators, were one of the causes of great concern for the authorities; while they may have boosted the morale of some, they were also a drain on valuable human and material resources. Eventually, the government put restrictions on some popular sports such as horse racing, greyhound racing and soccer but not on those annual events in the nation’s sporting calendar around which the country traditionally united and which were thought of as important parts of British culture.

Oxford prepare to launch

(Credit: The Isle of Ely Rowing Club)

The holding of wartime versions of the FA Cup, the Derby, cricket at Lord’s and the Oxford - Cambridge Boat Race provided a reassuring sense of familiarity during a time of national danger and widespread anxiety, reminding the public that what were thought of as essentially British values still endured and that they were worth fighting for.

During the 1939 - 1945 War, there were four Oxford - Cambridge Boat Races, all unofficial and for which no “Blues” were awarded. However, they attracted great interest, were broadcast on the radio and filmed by the cinema newsreels, and attracted viewing crowds running into thousands, perhaps peaking at something between 7,000 and 10,000 in 1943. Even these very different wartime Boat Races continued to hold their appeal to all classes, from Eton to Esher to the East End, and were, as always, enthusiastically supported even by those with no rowing or Oxbridge connections.

The race was held on neutral waters at Henley in both 1940 and 1945, on “Oxford waters” at Radley in 1943 and on “Cambridge waters” at Ely in 1944. All of them ran for just 1 1/4 to 1 1/2 miles, a shorter distance than the traditional 4 1/4 miles but far enough for undertrained and underfed crews. By the end of the war, the overall result was two-all and film of all the races can nowadays be viewed on YouTube.

CUBC crew photographed on 26 February 1944

(Credit: Christine Churcher)

Most sources claim that the failure to hold races in 1941 and 1942 was due to wartime logistical problems or to an inability to raise crews. However, in a letter to the Times in 1945, the Cambridge President during those years held that the gap was because the two universities could not agree conditions, notably there was a problem over the Dark Blue’s alleged insistence that the maximum age of a competitor should be 19. Possibly out of frustration, in 1942 Cambridge accepted a challenge from Imperial College, London, to a race from Putney to Hammersmith, a contest which the men from the Cam won.

It is reasonable to wonder why men who were fit enough for competitive rowing were not serving in the armed forces; this was because students of essential subjects such as medicine had “reserved status” and their courses were compressed and intensified. So that studies would not suffer, both universities agreed to limit training outings to three times a week, going up to four in the last month.

Even for those not attempting to represent their university, truncated college rowing and bump racing continued on both the Cam and the Isis during the war. Further afield, regattas were organised all over the country as part of the “Holidays at Home” drive, such events short on young men but providing plenty of racing for women, juniors and veterans. On the Thames Tideway, twenty-four eights took part in the only wartime Head of the River Race, Chiswick to Putney, on 25 March 1944.

“The Home Guard ran a telephone line along the course and the finish judge perched precariously atop a step ladder.”

Wartime privations intruded on all aspects of life, including Boat Race training. In 1940, The Scotsman noted that, “no expenses in connection with this year’s race can be borne by the University boat clubs”. Fuel rationing usually limited travelling beyond the Cam or the Isis and the local “petrol controller” refused fuel for coaching or press launches.

Food rationing made serious rowing very difficult. Stodgy wartime diets provide enough carbohydrate for the average person but oarsmen were constantly hungry. Adequate protein was a particular problem, adults were limited to one egg, 2oz cheese and about two chops worth of meat a week. In 1944, a story that the press widely reported concerned a parcel that the Oxford crew in training had received from a generous supporter - it contained a single orange.

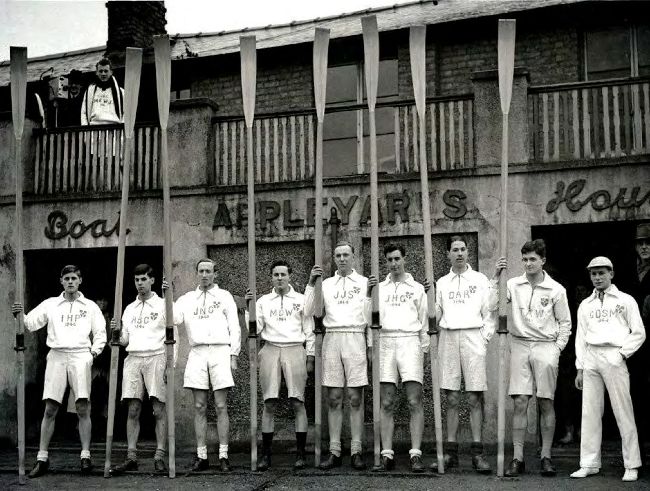

OUBC crew

In late 1943, agreement was made for a third wartime race, this to be held on 26 February 1944 at Ely on the oneand-a-half mile ‘Adelaide Course’ of the River Great Ouse, from the River Lark tributary to Adelaide Bridge. The straight course was fair for side-by-side racing and Cambridge had long used it for Blue Boat trials and for training prior to moving to Putney for final Boat Race practice.

Oxford arrived at Ely three days before the race, bringing their own oars but borrowing a boat from Cambridge. Boating was out of Appleyard’s Boathouse, now a restaurant. Average weights were about 11 stone 9 pounds for Oxford and 12 stone 1 pound for Cambridge though individual oarsmen varied from 10 stone 10 pounds to 14 stone 2 pounds.

The Times thought Ely “so isolated that few spectators are expected”, the newspaper ignoring the indefatigable appeal of the race and also that Britain was a vast military camp with millions of bored men waiting to embark for the D-Day invasion of Europe.

“Stodgy wartime diets provide enough carbohydrate for t

he average person but oarsmen were constantly hungry.”

The fact that a Boat Race was actually occurring in wartime was probably more important than the contest itself - or even the final result. Thus, the best record of race day 1944 was by someone who actually wrote very little about the rowing but a lot about the atmosphere. He was a sports columnist calling himself “The Twelfth Man”. He began by stating that, “All things considered, I suppose the (1944) Varsity boat race will go down in rowing history as about the strangest in the whole series…” Clearly, he never considered an even stranger future Boat Race – one with no spectators. Man Number Twelve continued:

(Rowed) far from its old peace-time home on the Thames Tideway, this time in the very heart of the Fen country, on an isolated stretch of the Great Ouse, it still drew thousands of spectators, a great tribute to the hold the race has on the nation. They came not only from the cathedral city of Ely, but from Cambridge, military and Air Force units and surrounding villages. All manner of transport was used - lorries, horses, a few cars, bicycles (push and motor), and Shanks’s pony involving miles of foot slogging. Convalescent airmen filled a hastily improvised grand stand of chairs set out on the tow path right opposite the winning post, American troopers gathered on banks behind and Australian airmen filled in points of vantage…

CUBC paddle out

(Credit: The Isle of Ely Rowing Club).

The Twelfth Man records that, although a dark blue flag marked the finish, because of Ely’s proximity to Cambridge, “light blue naturally predominated” and the crowd engaged in mock booing and hissing of the Oxford crew as they paddled down to the start. The Home Guard ran a telephone line along the course, the finish judge perched precariously atop a step ladder, the police abandoned an attempt to maintain a ticket-only section and the umpire followed the race on horseback.

Everyone who got to the race regarded it as distinctly an occasion… This very youthful boat race crowd, full of servicemen, about 5000 strong, against the millions who lined the Thames banks in peacetime, reproduced the typical humour of the old gatherings…

As to the actual race, Cambridge had led off the start, withstood a couple of bursts from Oxford and were still a quarter of a length in front past the half-way mark. However, according to the Times, “a sharp half-minute by Oxford, who raised the stroke to 38, brought them level, and soon after this Cambridge began to fall back, showing signs of getting short while Oxford were much more steady”. Oxford won by three-quarters of a length in eight minutes and six-seconds, gaining their second success in the third of the wartime Boat Races.

“The Times thought Ely ‘so isolated that few spectators are expected’, the newspaper ignoring that Britain was a vast military camp with millions of bored men.”

The Twelfth Man penned these final words on the Boat Race of 1944:

None of the American soldiers at Ely had ever seen the race before and naturally knew little of its standing in this country or long history. One who came from Utah, intrigued me by suggesting that there ought, “To be more boats in the race,” adding “But perhaps it was some sort of final!” But even he was very impressed by the racing and voted it “Swell.”

Even after 77 years, we surely must agree with the Utahan GI. Be it rowed on the Thames Tideway or on the Great Ouse, be it taking place during a world war or during a global pandemic, be it held in 1944 or in 2021, the Oxford - Cambridge Boat Race is always a swell event.